The German Renaissance, part of the Northern Renaissance, was a cultural and artistic movement that spread among German thinkers in the 15th and 16th centuries, which developed from the Italian Renaissance. Many areas of the arts and sciences were influenced, notably by the spread of Renaissance humanism to the various German states and principalities. There were many advances made in the fields of architecture, the arts, and the sciences. Germany produced two developments that were to dominate the 16th century all over Europe: printing and the Protestant Reformation.

One of the most important German humanists was Konrad Celtis (1459–1508). Celtis studied at Cologne and Heidelberg, and later travelled throughout Italy collecting Latin and Greek manuscripts. Heavily influenced by Tacitus, he used the Germania to introduce German history and geography. Another important figure was Johann Reuchlin (1455–1522) who studied in various places in Italy and later taught Greek. He studied the Hebrew language, aiming to purify Christianity, but encountered resistance from the church.

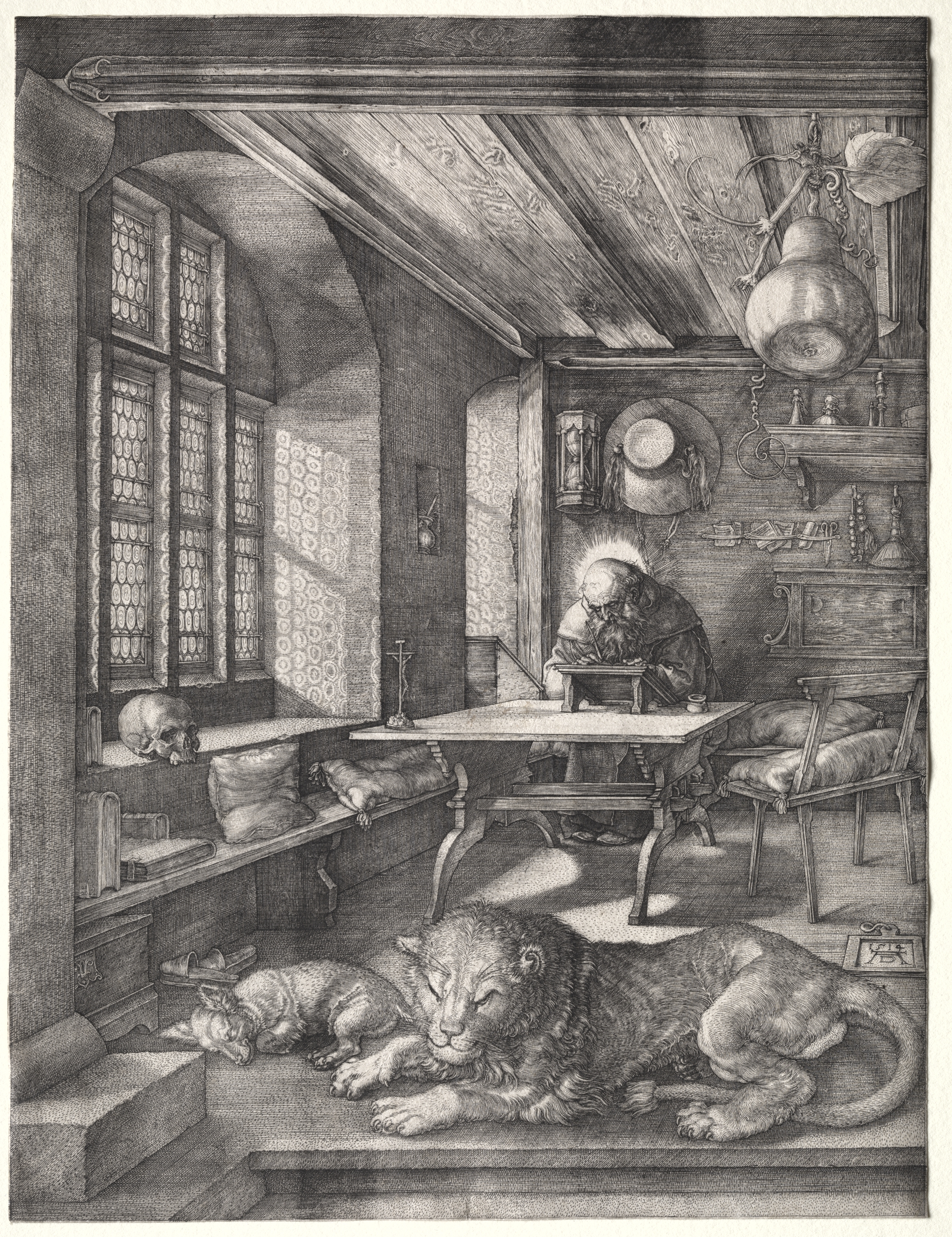

The most significant German Renaissance artist is Albrecht Dürer especially known for his printmaking in woodcut and engraving, which spread all over Europe, drawings, and painted portraits. Important architecture of this period includes the Landshut Residence, Heidelberg Castle, the Augsburg Town Hall as well as the Antiquarium of the Munich Residenz in Munich, the largest Renaissance hall north of the Alps.

German Renaissance art was vibrant, innovative, and at times powerfully emotional. “German,” as used here, refers to a linguistic rather than a political region that encompassed much of the former Holy Roman Empire, including today’s Austria, Germany, and Switzerland as well as parts of the Czech Republic, France, and Poland. The period from c. 1400 to c. 1600 bears multiple and often overlapping names, such as late Gothic, Renaissance, mannerism, early modern, or between Renaissance and Baroque.

Albrecht Dürer (b. 1471–d. 1528), the most famous German artist regardless of century, belonged to a generation of exceptionally inventive masters, including Albrecht Altdorfer, Hans Baldung Grien, Hans Burgkmair, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Matthias Grünewald, Hans Holbein the Elder, Hans Holbein the Younger, and Tilman Riemenschneider. Their art embodied a spiritually intense and highly material religiosity. Most responded creatively to the nascent Protestant Reformation’s challenge to the traditional roles of religious art or to the incorporation of new antique-inspired stylistic features in their oeuvres. They represent just one moment in a highly diverse history.

Cities such as Augsburg, Nuremberg, and Cologne were important artistic centers throughout this period. Mercantile towns such as Lübeck and Ulm flourished in the 15th century, while Wittenberg, Dresden, and Munich came to prominence only in the 16th century as the power of the rulers of Saxony or Bavaria grew. Johann Gutenberg’s invention of movable type initiated a revolution in how information was presented and disseminated across Europe. The advent of printed books coincides with the earlier development of woodcuts, engravings, and other forms of prints pioneered by German masters.

Inexpensive to make and buy, prints reached wider and more socially diverse audiences than paintings or sculptures. The medium encouraged the rise of new subjects and the dissemination of artistic ideas, such as the spread of early Netherlandish art throughout Germany. Although much of their art is lost, goldsmiths in Augsburg, Nuremberg, and other centers were famed for their technical skills and creative designs. Wooden sculptures, from huge altarpieces to masterfully carved statues, filled German churches prior to the Reformation. Masters such as Michael Pacher, Riemenschneider, Veit Stoss, Hans Leinberger, or Master H. L. made wood do seemingly impossible things as they devised complex draperies and expressive figural poses. Later sculptors, responding to the Reformation and then the Catholic Reformation in the last quarter of the 16th century, diversified their production to include portraits, fountains, collectible objects, and sometimes monumental tombs.

Leave a comment