On Friday, June 6, 2025, NYC Department of Transportation in partnership with artist Fitgi Saint-Louis and the West Harlem Art Fund will unveil the sculp- ture “Aunties” on the 124th Street and Lenox Avenue median. The work presents three figures, each standing 6.5 feet high, 6 inches deep, and 16 inches wide. This sculpture is composed of hollow CNC milled layers of wood that has been fine sanded and painted. Assisting the artist Fitgi Saint-Louis is Brooklyn-based woodworker Kevin Carlin.

As described by Saint-Louis “Aunties honors the women within our lives who passionate- ly nurture and embolden our community. In Harlem these cultivators of culture, orga- nizers and style icons, have fearlessly called us to action across generations.”

Here we wish to honor the various women who have walked the streets of Harlem and made the community — East, Central and West Harlem remembered.

- Ella Baker, Civil Rights activist

- Kay Brown, novelist and artist

- Evelyn Cunningham, journalist

- Lorraine Hansberry, writer

- Gwendolyn Knight, artist

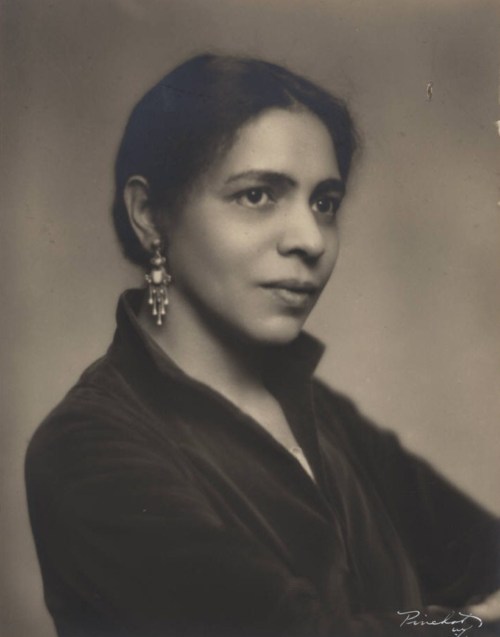

- Nella Larsen, writer

- Mae Mallory, activist

- Una Mulzac, bookseller

- Luisa Moreno, labor organizer

- Rita Moreno, film actress

- Louise Thompson Patterson, social activist and professor

Ella Baker (born December 13, 1903, Norfolk, Virginia, U.S.—died December 13, 1986, New York, New York) was an American community organizer and political activist who brought her skills and principles to bear in the founding of major civil rights organizations of the mid-20th century. She is widely recognized as one of the key leaders of the American civil rights movement.

Kay Brown (1932–2012) was an African American artist, Printmaker, published author, Graphic and Fashion designer. She graduated at New York City College in 1968, with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. She was also a graduate at Howard University in 1986 with a Master of Fine Arts degree. Brown became the first woman awarded a membership into the Weusi Artist Collective, based in Harlem during the 1960s and 1970s. The Weusi Collective, named for the Swahili word for “blackness”, was founded in 1965, composed entirely of men. The fact that she was the only female member of this collective inspired her to seek out ways of representing the neglected Black female artists. She is widely acknowledged as one of the founders of the Where We At Black women artists’ collective in New York City. Brown’s works are credited for representing issues that affected the global Black community via her mixed media collages and prints. Brown’s work was featured in the “We Wanted a Revolution” exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum.

The field of journalism has been essential to broadcasting many historical events over time. Journalists have a long list of very important responsibilities they are accountable for—most notably, to tell the truth about what happens in our world. In times of great societal upheaval, there tend to be polarizing groups with equally polarizing views. Oppressive groups seek to control the media, while oppressed groups want to have their experience told. This was the case when journalist Evelyn Cunningham rose to prominence during the Civil Rights Movement. Throughout her career, she worked as a reporter, radio host, special assistant to and leader of an office on women’s affairs for Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Furthermore, she founded an advocacy group called “The National Coalition of 100 Black Women” in 1981. However, while I would love to write about the entirety of her illustrious work history, I will focus on her work as a journalist and radio host, in which she worked hard to tell the stories of Black activists and important events regarding the Civil Rights Movement.

Cunningham was born on Jan. 25, 1916, in North Carolina. When Cunningham was still a child, the family moved to New York City, where she attended elementary and middle school. From here, she would go on to attend college and earn a bachelor’s degree in social sciences in 1943, also attending the Columbia University School of Journalism and the New York School of Interior Design at different points. With the skills she learned in higher education, Cunningham went on to work as a reporter, columnist, and editor for the Pittsburgh Courier—a prominent Black newspaper at the time—from approximately 1940 to 1962. In 1961, Cunningham started a radio show called “At Home with Evelyn Cunningham,” which reported on events occurring across the country—especially those regarding the Civil Rights Movement. Most notably, she covered the work being done by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other prominent activists like Malcolm X.

Over the course of her career, Cunningham was forced to deal with sexist and racist oppression from her counterparts and potential consumers of her content. Cunningham married four times, never having any children, often complaining about how men tried to rob her of her independence. As a Black woman in the field of journalism, Cunningham shined a bright light on the issues Black people were facing, offering a space for our voice to be heard more truly and clearly than in white journalistic spaces. Furthermore, just by being a Black woman in the space, she opened doors for both women and Black people to enter the journalistic space in the future.

Cunningham leaves behind no children but a vastly magnificent and multifaceted legacy. She was awarded many awards over the course of her career, including New York City’s Century Club’s Women of the Year Award and the Abyssinian Development Corporation’s Harlem Renaissance Award in 1998. Overall, Evelyn Cunningham had a career that was unprecedented in excellence and historical impact, and she deserves every accolade she has received.

Lorraine Vivian Hansberry (May 19, 1930 – January 12, 1965) was an American playwright and writer. She was the first African-American female author to have a play performed on Broadway. Her best-known work, the play A Raisin in the Sun, highlights the lives of black Americans in Chicago living under racial segregation. The title of the play was taken from the poem “Harlem” by Langston Hughes: “What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?” At the age of 29, she won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award – making her the first African-American dramatist, the fifth woman, and the youngest playwright to do so Hansberry’s family had struggled against segregation, challenging a restrictive covenant in the 1940 U.S. Supreme Court case Hansberry v. Lee.

Gwendolyn Clarine Knight (May 26, 1913 – February 18, 2005) was an American artist who was born in Bridgetown, Barbados, in the West Indies.Knight painted throughout her life but did not start seriously exhibiting her work until the 1970s. Her first retrospective was put on when she was nearly 90 years old, “Never Late for Heaven: The Art of Gwen Knight,” at the Tacoma Art Museum in 2003.[2] Her teachers in the arts included the sculptor Augusta Savage (who obtained support for her from the Works Progress Administration) and Jacob Lawrence, whom she married in 1941 and remained married to until his death in 2000.[3] During the course of her career, she received many awards, including the National Honor Award, and two honorary doctorate degrees, from University of Minnesota and Seattle University.

With her husband, Knight founded the Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation in 2000, initially to support the early careers of professional artists. When Lawrence died, Knight disbanded the original foundation and changed her will so that most of the couple’s assets went to support children’s programs. Today the Foundation’s activities are devoted to the maintenance of a website that had been developed in 2000.[4] The U.S. copyright representative for the Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation is the Artists Rights Society.

Nella Larsen (born April 13, 1891, in Chicago, Illinois; died March 30, 1964, in New York City) was an American novelist and short-story writer associated with the Harlem Renaissance. She was born to a Danish mother and a West Indian father, who died when she was two years old. Larsen is best known for her novels “Quicksand” (1928) and “Passing” (1929), which explore themes of race, identity, and gender. Her work is celebrated for its psychological depth and formal polish, making significant contributions to African American literature.

Mae Mallory (June 9, 1927 – 2007) was an activist of the Civil Rights Movement and a Black Power movement leader active in the 1950s and 1960s. She is best known as an advocate of school desegregation and of black armed self-defense.

By 1955, Mae Mallory’s two children were enrolled in the New York City public school system. At this point, in 70 percent of NYC public schools, over 85 percent of students were racially homogeneous. The city’s zoning policies created a system where schools were racially segregated by mirroring the neighborhoods’ lack of diversity. Although racial segregation within the school system was prohibited by law, schools were still affected by racial separation, meaning that Black and Latino children were receiving a second-class education.

In 1956, Mallory became founder and spokesperson of the “Harlem 9”, a group of African-American mothers who protested the inferior and inadequate conditions in segregated New York City schools. group was originally called “the Little Rock Nine of Harlem”, however, it was eventually shortened to the “Harlem 9.”

Inspired by a report by Kenneth and Mamie Clark on inexperienced teachers, overcrowded classrooms, dilapidated conditions, and gerrymandering to promote segregation in New York, the group sought to transfer their children to integrated schools that offered higher quality resources.

“Harlem 9” activism included lawsuits against the city and state, filed with the help of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). By 1958 it escalated to public protests and a 162-day boycott involving 10,000 parents. The boycott campaign did not win formal support from the NAACP, but was assisted by leaders such as Ella Baker and Adam Clayton Powell, and endorsed by African-American newspapers such as the Amsterdam News. While the children were engaged in another boycott in 1960, the campaign established some of the first Freedom Schools of the civil rights movement to educate them.

New York City retaliated against the mothers, trying and failing to prosecute them for negligence. In 1960, Mallory and the Harlem 9 won their lawsuit, and the Board of Education allowed them, and over a thousand other parents, to transfer their children to integrated schools. That year, the Board of Education announced a general policy of Open Enrollment, and thousands more black children transferred to integrated schools over the next five years. (Overall integration in the city was thwarted, however, by the practice of white flight.)

Una Mulzac was born on April 19, 1923 in Baltimore and moved to the Bedford Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, NY as a little girl. She graduated from Girls High School, where she ran track, and got a secretarial job at Random House, where she became interested in publishing. She moved to Guyana, then known as British Guiana, around 1962 to start a bookstore and to work for the party of Cheddi Jagan, a revolutionary Marxist. While in Guyana, she escaped death when a package arrived at the bookstore in Guyana. A colleague opened it and was killed, she suffered wounds to an eye and her chest. She came back to the US and then returned to Guyana.

Discouraged by the conservative government that came to power after Guyana gained independence from Britain in 1966, she returned to Harlem, deciding to pursue revolution by other means. She opened her bookstore in 1967. Ms. Mulzac’s profession was selling books at Liberation Bookstore, a Harlem landmark that for four decades specialized in materials promoting black identity and black power. On one side of the front door, a sign declared, “If you don’t know, learn. On the other: If you know, teach.” Soon books were piled atop revolutionary pamphlets amid posters of black political heroes.

Her bookstore, born at a time when Harlem was ravaged by crime and heroin, became a neighborhood landmark like the Apollo or Sylvia’s Restaurant and endured into the era of Starbucks and Old Navy. People came from all over Harlem and beyond to buy books there, whether by well-known authors like James Baldwin and Toni Morrison or by little-known conspiracy theorists.

Luisa Moreno (born August 30, 1906, Guatemala City, Guatemala—died November 3, 1992, Guatemala) was a Guatemalan-born labour organizer and civil rights activist who, over the course of a 20-year career in public life, became one of the most prominent Latina women in the international workers’ rights movement.

Blanca Rosa Lopez Rodrigues was born to an upper-class family in Guatemala and attended primary school in Oakland, California. She returned to Guatemala as a teenager, but she was unable to continue her education, because women were not permitted to enroll in Guatemalan universities at that time. In response, she organized a group to lobby for female students to be included in higher education. Having developed an interest in social issues, she later moved to Mexico City, where she worked as a reporter for a Guatemalan newspaper.

In 1928 she moved to New York City, where she supported her husband, an artist, and her infant daughter by working as a seamstress in a garment factory. She was outraged by the garment industry’s harsh working conditions and low wages as well as by the extent of racial segregation and discrimination in the United States. She soon became involved with a group of Latino labour activists and participated in several strikes. In 1930 she joined the Communist Party. About that time she adopted the name Luisa Moreno so as to disassociate her family from her political positions and labour activities, of which they disapproved.

In 1935 the American Federation of Labor (AFL) hired her as a professional organizer and the next year assigned her to organize Florida tobacco workers. She later broke with the AFL and joined the newly formed Unified Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA; also called the FTA, or Food, Tobacco, Agricultural, and Allied Workers of America), which was affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). She was soon elected to the CIO council and became its first woman and first Latino member. She was named the international vice president of the UCAPAWA in 1941 and traveled to southern California to organize labour at food-processing plants. During that time she helped organize numerous labour affiliates of the UCAPAWA, including unionizing Local 2 of Fullerton, California, at the largest cannery in southern California at the time. In 1943 she and Dixie Tiller founded the Citrus Workers Organizing Committee in Riverside and Redlands, California.

Rita Moreno (born December 11, 1931, Humacao, Puerto Rico) is a Puerto Rican-born American actress, dancer, and singer who accomplished the rare feat of winning the four major North American entertainment awards (EGOT): Emmy (1977, 1978), Grammy (1972), Oscar (1962), and Tony (1975). She was also the first Hispanic woman to receive an Oscar (Academy Award).

After her parents divorced, Alverio moved (1935) to New York City with her mother, who eventually remarried. She later began using her stepfather’s surname, Moreno. As a youth, she took dance lessons, and she later dubbed voices for American child stars in films released to Spanish-speaking countries. In 1945, at age 13, she made her Broadway debut in Skydrift. Her first big-screen appearance was in So Young, So Bad (1950). She was credited as Rosita Moreno, but soon thereafter she took the first name Rita.

Although Moreno subsequently appeared in several notable films—including the musicals Singin’ in the Rain (1952) and The King and I (1956), playing a starlet and a slave, respectively—her early career was hampered by studios wanting to cast her in stereotypical ethnic roles or as a sexpot. Partly because of professional frustrations—though largely because of a tumultuous relationship with Marlon Brando—she attempted suicide in 1961. That year, however, Moreno received critical acclaim as the fiery and cynical Anita in West Side Story. For her performance—which highlighted her energetic dancing—Moreno won an Academy Award for best supporting actress. (Although she was a singer, her singing voice was dubbed in the movie.) The musical drama was named best picture. Despite the success, Moreno continued to struggle for good roles, and her film work was limited. Later movies included Summer and Smoke (1961), Carnal Knowledge (1971), and Slums of Beverly Hills (1998). In 2021 she appeared in Steven Spielberg’s acclaimed remake of West Side Story, and two years later she joined an all-star cast—that included Jane Fonda, Sally Field, and Lily Tomlin—in 80 for Brady, a comedy about a group of friends whose love for the New England Patriots and star quarterback Tom Brady leads to a raucous Super Bowl weekend.

Louise Thompson Patterson, a social activist who was the last remaining survivor of the cultural movement known as the Harlem Renaissance and a longtime associate of poet and playwright Langston Hughes, died Aug. 27 in New York. She was 97.

A Chicago native who was reared in the West, Patterson was one of the first black graduates of UC Berkeley, earning a degree in business administration in 1923. She later joined the faculty of Virginia’s Hampton Institute, a black college with a predominantly white teaching staff and administration that boasted as its star pupil Booker T. Washington, who would later found Tuskegee Institute.

In 1927, Patterson supported a strike against Hampton’s paternalistic policies, which included a lighted cinema to prevent necking and Sunday serenades of white visitors with plantation songs.

Described by scholar Faith Berry as “too proud of her race not to be a part of it,” Patterson moved to New York the next year, drawn to the intellectual and creative ferment of the 1920s and 1930s that became known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Harlem in the ‘20s was called the capital of the black world, the crossroads for an explosion of cultural awareness among American blacks. The movement produced great achievements in the arts, from the music of Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong to the writing of Zora Neale Hurston, Wallace Thurman and Hughes, who earned belated recognition as the poet laureate of that golden era.

Patterson was not an artist–she came to New York on an Urban League fellowship to study social work–but she became a central figure in the movement. Described as beautiful and intelligent in historical accounts of the era, she quickly made her mark on the Harlem scene. She married Thurman, the writer and leading bohemian intellectual, soon after her arrival (and separated from him about six months later). Later, she formed a salon called Vanguard that attracted Harlem artists with concerts, dances and discussions of Marxist theory.

A lifelong friendship with Hughes began when Patterson was hired as his stenographer on a play called “Mule Bone,” which he co-wrote with Hurston, another leading figure of the Harlem cultural movement. Hughes and Hurston had hoped that the folk comedy, written in rural black dialect, would alter the course of black theater in 1931 when it was scheduled for production.

But “Mule Bone” became a bone of contention between its authors, whose partnership collapsed because of Hurston’s jealousy of Patterson. The play was never finished, though Hurston later tried to peddle it as solely her own.

The Hughes-Hurston collaboration “represented the aspirations of the Harlem Renaissance,” wrote historian Steven Watson, and its breakup “reflect[ed] the movement’s end.”

Leave a comment