Metal Workers in Harlem by Ben LaRocca

Jackie Robinson, St. Nicholas and Morningside Parks, Harlem through October 30, 2025

I once had the pleasure of sitting on an uptown patio with Leo Steinberg, the Russian-born old world intellectual who became an influential voice in 20th century modernism. Looking at the trees reaching high overhead and framing our little sitting area, he commented, “It’s hard for any sculpture to compare with the natural grandeur of a tree.” Heading uptown 20 years later, his words returned to me as I considered the reason for my trip: eleven discrete metalwork sculptures by 10 different artists spread across three parks in Harlem, the latest event in Harlem Sculpture Gardens and The West Harlem Art Fund’s ongoing engagement with our municipal public grounds here in New York City.

I started my jouI started my journey at 147th street and Jackie Robinson Park, the northernmost of the three parks in Harlem I intended to visit, with a sculpture called “Harlequin,” by Michael Poast. Poast conjures old time feelings for the Harlem Renaissance in high modernist form: carnival, the original home of the harlequin. To find “Harlequin,” I I had to skirt the Jackie Robinson Pool, a product of the WPA from 1936, its characteristic scale dwarfing everything around it, a blocky massiveness emphasizing the quick, provisional line work of Poast’s cut steel.

Just around the corner, the play of steel continued in Carol Eisner’s mysteriously titled “Chiara.” My best guess is that she is speaking Italian: chiara means “clear” from the latin clara, meaning bright or colorful. Is that a clue to the sculpture’s meaning? I think so considering its enamel greens, blues and purples shimmering in the sunlight, its round forms curving in on one another, it seems to curl inward on itself. To find Chiara’s pop colors resonating at the back of the great public pool, I walked past Margaret Roleke’s “Tower,” which is not so much a tower as a block, the white steel frame for which supports a seemingly infinite supply of colorful shell casings, their bright plastic echoing Eisner’s colors. Here is an invocation of fire, which underlies all steel work, an ominously contemporary nod to the elemental foundations of the substance of the exhibition.

I’m now well prepared for the next step in my meandering journey 7 blocks to the south at St Nicholas Park where first sculpture we find begins to suggest a rhythm to the spatial narrative played out in this well-curated exhibition: Richard Brachman’s “Drums of War” answers the call of Eisner’s “Tower,” politically repurposed oil drums musically strung with quotes from notables such as Joseph Heller and JuliusCesar, their words bearing topically on the evils of war.

The sounds of battle fading uptown, I encounter the second most formidable architectural wonder of my journey: the broad reaches of St. Nicholas Park’s climbing stairs spanning portions of lands that once housed the Old Croton Aqueduct, a massive 19th century land works project engineered to bring water to the island of Manhattan from the Groton Dam in Westchester. From our focus today on quick architecture with quicker attention spans, an undertaking like this seems worthy of the Holy Roman Empire, which is not far off and tells us a great deal about the scale with which we imagined our communal projects of the 19th century, drawing attention, in tern, to the modest, human size scale of the sculptures I’ve been seeing.

As if to underscore this, David Karoff’s bronze “Horizontal Figure,” which lies between 138th and 139th streets, below the stairs of St. Nicholas. It is the first work in the show that refuses to declare itself against the landscape, its counter-supine form seems about to sink into the earth, horizontal figure indeed, its presence a welcome respite, a reminder of the sacred bond between earth and fire. Above it on the green we find the tesseract-like form of Miller’s aluminum “Tethered Diffusion” shimmering in the sunlight. Unfortunately the electrical feed to Miller’s form was inactive at the time of my visit. Perhaps it was on a timer, a nocturnal sculpture by nature. Leaving St. Nicholas, the bright orange of David Sheldon’s “Canary” is hard to miss, a reprise of the light cut steel line present also in Poast’s work and a patterned accent to the exhibition as a whole, and a reminder of one of the late greats of cut steel: George Sugarman.

The theme is brought to a natural close with Poast’s “Bronco” 20 blocks south in Morningside Park, the last stop on my morning pilgrimage. As I circumambulated, I lightly bumped my head on one of the sculpture’s outstretched reaches and had the pleasure of feeling it vibrate lightly around me: what fun! Further vibrations were in store a few blocks south with Michael Levchenko’s “Post Tango,” a rippling pinkintervention in the summer greens of Morningside, the sculpture seems in conversation with the narrow footpath it flanks, its movement speaking to the rhythmic wave theory Manhattan’s pedestrian legion.

A few blocks further south I am once again reflecting on Steinberg’s old idea about nature and sculptures, now feeling the vastness of the island of Manhattan beneath my feet in the forms of humans’ architectural responses to it, among which nestled the 12 sculptures I had come to see. Perhaps their purpose was never to rival their surroundings at all. Instead their forms are intimately scaled to the size of our bodies, nevermeant to overwhelm or impress, rather intended to provoke thought and feeling. I became aware of the inclusiveness of the Harlem Sculpture Garden, open to these diverse, quiet voices.

The final two sculptures I encountered seem to underscore this sort of thinking. Graciela Cassel’s “Romance in the Garden” a trio of trellised benches set back under the trees and offering orange succor to the tired wayfarer, were an opportunity in which I gladly would have partaken had the seats not already been occupied. Building more places to sit down in the city? Shouldn’t every sculptor be doing this? Thank you Graciela! The interactive, open-endedness of “Place of the Rushes” by Peter Miller completes my viewing of this exhibition. This is a collaborative work expressive of indigenous presence in the likeness of a woman’s visage cast of a multiplicity of variously modeled blue plastic. It is a work that mixes the martial feel of our urban metropolis with a sentiment for something much more ancient and firmly rooted in earth and tradition: a project appropriate to a place like Harlem.

Dream Orbs and Fractured Seals: Two Artists in Harlem

An interview with Abigail Regner and Joseph Bochynski on their sculptures in Harlem Sculpture Gardens

Joe: Abigail, tell me about your piece that’s up at the Harlem Sculpture Garden this summer.

Abigail: My piece is called The Community Dream Orb. It’s a sculpture I built in collaboration with Harlem and New York City community members. The Orb was started during a residency at the Urban Soil Institute on Governor’s Island, where I led a three-day workshop. People came, added their own creations, and followed a prompt I developed around “amulet making.” I asked them: What objects, symbols, or figures guide you into your future? The results were incredible—about a hundred unique pieces now cover the Orb, each carrying someone’s vision or hope. It’s really a monument to collective dreaming.

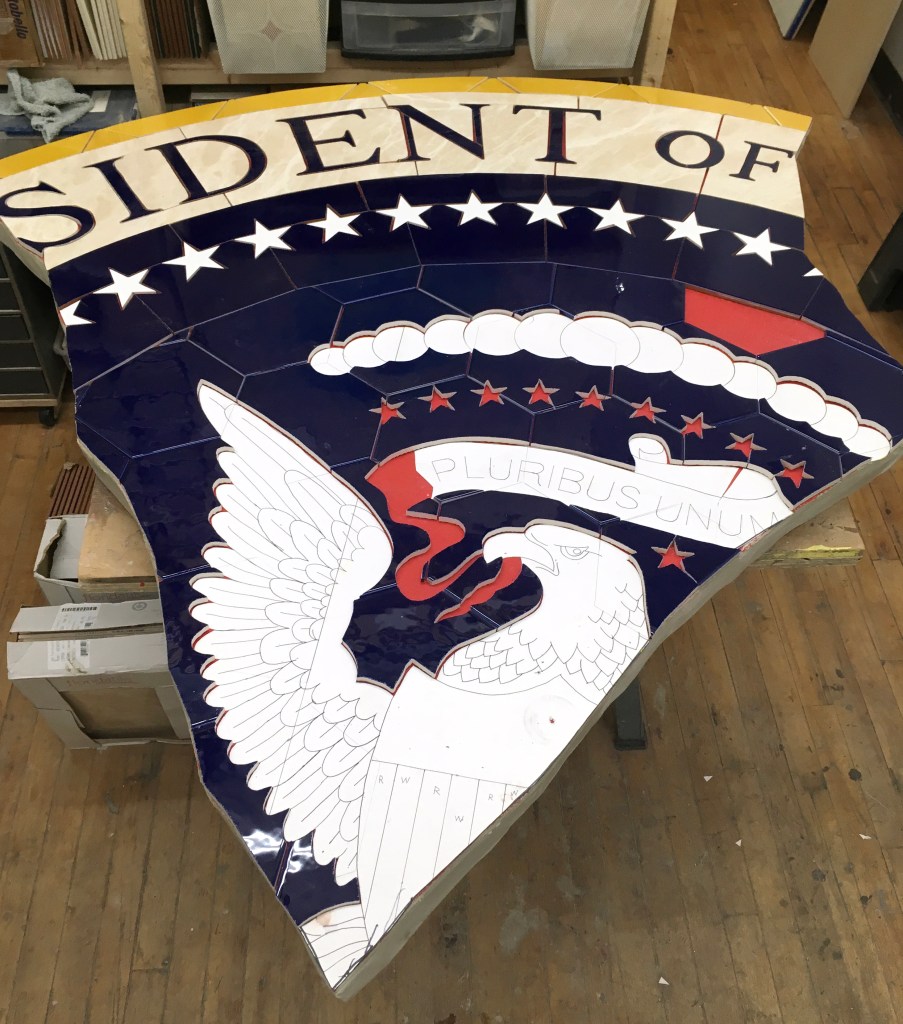

Joe: That’s beautiful. My piece shares some of that symbolism, though it takes a different turn. Discoveries in Democracy is a ceramic tile mosaic of the Presidential seal, fractured and incomplete. The fragments span eight or nine feet across when whole, but in St. Nicholas Park you only see pieces, as if unearthed or sinking back into the ground. For me, it speaks to the fragility—and possible deterioration—of institutions I once thought unshakable. Of course, others may read it as the resurgence of executive power, which is part of what I love about public art: it invites multiple, even conflicting, interpretations.

On Material and Meaning

Joe: Both of us chose ceramics, which carries its own tension—permanent yet fragile. How did that play into your decision?

Abigail: I did worry about bringing ceramics into a public park, knowing it could be damaged. But clay felt essential. Across history, clay has been about community—people eating, drinking, and sharing stories together. For this project, clay symbolizes connection and preservation, almost like freezing this collective moment in time. And honestly, because the community helped build the Orb, I felt it belonged in the community, even if that meant accepting risk. If someone breaks it, that’s still part of its life.

Joe: I love that perspective. For me, the brokenness was intentional from the start. The Presidential seal fragments are half-buried, durable but vulnerable. If someone defaces or alters it, I see that as an extension of the piece—a reflection of their political expression rather than an attack on the work itself.

Public Space vs. the Gallery

Abigail: It’s a big leap, letting go of control when art goes into public space. How does that shift feel for you?

Joe: Stressful at first! In the studio I want to manage how people see and interpret my work. In public, you give that up—but you also get something richer. People stumble on it unexpectedly, without gallery walls telling them how to behave. That discovery, I think, has a power of its own.

Abigail: Exactly. And accessibility is central to me. Many people I engage with in Harlem don’t feel comfortable walking into galleries. By placing the Orb in the park, it removes that barrier—it’s theirs, as much as mine. In galleries, I think my work might be classified more as “participatory” or even “performance,” but the park makes it more democratic.

Joe: I agree. If contemporary art isolates itself too much, it risks irrelevance. Bringing work back into shared spaces like Harlem’s parks is one way to mend the gap between artists and the public.

Histories, Stories, and Symbols

Joe: Is there anything in the history of ceramics that informed your approach?

Abigail: Definitely. Ceramics are rooted in vessel-making—objects that hold what we need, that facilitate sharing. The Orb draws on that. I’m also fascinated by infinity forms: circles, chains, toruses. They kept appearing in what people added. For me, infinity is grounding—it’s a truth that ties into larger existential questions about life, time, and how we move forward.

Joe: That resonates. I came back to narrative in my work after having kids, realizing how stories shape our understanding of the world. Cycles—beginnings that return to endings—are one of the most compelling story structures. And symbols, whether mythic or political, live in both our dreams and waking lives.

Abigail: That’s why I find your mosaics so compelling. The fragments feel architectural, geometric, almost medieval, but also playful, almost like tessellated patterns you’d see in Islamic tilework. They carry authority but subvert it too.

Joe: Exactly. Ceramic tile often connotes permanence—subway walls, civic buildings, even religious spaces. By fracturing and re-contextualizing it, I’m asking viewers to reconsider that authority, to see fragility in what seems immutable.

Looking Forward

Abigail: So where do you see your work living—gallery, museum, or public spaces?

Joe: Ideally, all of the above. But children remind me most why accessibility matters. They walk into a museum, see a painting, and say something adults are too conditioned to admit: the truth. They notice the humor, too, which is often missing in how adults “behave” around art. I want my work—whether in tile, park, or gallery—to reach a general audience, to catch their attention like a catchy song, then pull them deeper.

Abigail: I feel the same. The Dream Orb works best in community, where anyone can walk up to it and see themselves reflected. For me, art has to be accessible—or it loses its purpose.

Joe: Well said.

Abigail: And thank you—this has been such a great conversation.

Joe: Likewise. Two very different sculptures, but both about community, story, and the symbols we live by.

A Scavenger Hunt of West Harlem’s Wooden Sculptures (and Others): A Lesson in Community Arts Altruism

JUL 29, 2025

This year has been a transitional moment for me in developing a greater appreciation for sculpture. Prior to 2025, I had my admiration for the likes of Isamu Noguchi, Joel Shapiro, or Lee Bontecou, but this year hits differently as my respect for the medium seems to have grown about a hundred-fold as seen in the sculpture-centric projects I have taken on, from reviewing Westwood Gallery’s recent The Secret Sculptures of Andy Warhol & Victor Hugo exhibition for Whitehot Magazine to highlighting art critic Eric Gibson’s book The Necessity of Sculpture (2020) to hearing the sage insight of veteran sculptors like that of Leah Poller from the New York Society of Women Artists. And now we come to the Harlem Sculpture Gardens, a West Harlem-based arts program that hosts an annual sculpture exhibition featuring works by over 20 artists spread across the parks of the Morningside Heights, St. Nicholas, and Hamilton Heights neighborhoods in West Harlem.

An artist friend of mine found an open call for writers posted on the Instagram page for the West Harlem Sculpture Gardens in which they sought arts writers to cover their 2025 cohort of sculptors. Given the depths of my love for art, I am always open to new opportunities and was excited to potentially bring my writing to a different area of the New York art scene. Soon after applying, I spoke with the program’s Executive Director & Chief Curator, Savona Bailey-McClain, who went into great detail about the Harlem Sculpture Gardens’ initiatives to introduce new public sculptures by leading contemporary artists to be seen and appreciated by local communities. We hit it off immediately as the mission of democratizing arts accessibility is a core value she and I hold very dearly. Since the number of artists in the program is quite expansive, I was assigned to focus on the wooden sculptures (although I will discuss some of the non-wooden works that I happened to encounter in an Honorable Mentions section towards the end).

Art & Ponder by Liam Otero is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.Subscribe

St. Nicholas Park – Bridget Conway (American)

In the part of the park close to the grounds of City College, Bridget Conway’s Grid Lines (2025) is a large-scale, supine, gridded wooden sculpture that rests along a treeless stretch of grass easily noticeable along the winding path and the overlooking fenced side of St. Nicholas Terrace. Redolent of a number sign that lays on a diagonal, the thick beams of wood that hold the entire work together evoke a weightiness no different from that of an ancient tree and its shadeless position puts Grid Lines in full contact with the sun’s rays, which makes Conway’s sculpture feel naturally at home with its surroundings. Though it may be laying flat, the negative space in-between the gridded squares remains a shaded home for the grass while the outer, more exposed edges experience the day-by-day growth of new blades.

Savona sent me a video beforehand documenting the sculptor’s process in joining the pieces together. Conway applied the Japanese sculpting technique of shou sugi ban (also known as Yakisugi) through which the wooden pieces are burned, cleaned, and then oiled to ensure that it remains structurally durable – an all-natural process rendering the work resistant to weather conditions and wood-consuming insects. She used a hand-held torching device to burn the surfaces of each piece of wood, a process that gradually unfolds with the charring of the originally light tan wooden pieces into a charcoal black.

Conway’s attentiveness to materiality and technique stems from her interest in devising more eco-sustainable ways of conceptualizing sculptures as inspired by folk architecture and folk art methods. What I find incredibly inspiring about Conway’s Grid Lines is that the sculpture was conceived from wood that was then burned – a most literal baptism by fire – and finally situated in an open-air space. This is a work whose very existence is formed and affected by the elements – the earth upon which it rests, the fire that ensured its structural longevity, the wind that courses through its interior and exterior, and the rain that makes contact with the sculpture and floods through the inner holes whilst nourishing the grass. Conway’s sculpture is potently demonstrative of how a work of art can truly reside in a mutually harmonious relationship with nature.

The video Savona sent me of Conway adhering to the shou sugi ban method.

St. Nicholas Park – Fitgi Saint-Louis (Haitian-American) / Beam Center

Going further inland, Fitgi Saint-Louis’s Fe Limye (2025) is an acrylic painted wooden architectonic work whose colorful facade stands out from the high hill on which it resides. Similar in form to a church, the work’s facade is festooned in panels of vibrant shades divided by wooden borders – a decorative effect reminiscent of either Gothic stained glass windows or cloisonné metalwork. But instead, Saint-Louis’s aesthetic choices originate from a cornucopia of cultural allusions specific to Caribbean, African, and Latin American cultures: textile and quilting traditions of South America; ornately patterned West African compound facades; and Caribbean vernacular domestic architecture. The title is distinctly Haitian in origin as it relates to a native custom of creating fanal, small paper lanterns resembling buildings whose inner lights glow through the imitation windows. Though normally small and handheld-sized, Saint-Louis’s Fe Limye is the size of a small chapel and its colorful exterior transforms into a spectacular beacon to be seen from close-up and at a distance. Much like traditional fanal, her work becomes a source of illumination in the middle of the night, which allows the spectral panels to radiate in jeweled tones.

The synthesis of influences behind Saint-Louis’s Fe Limye is a reflection of the melting pot of cultures that define Harlem. To see such a magnificently executed work on the top of a hill overlooking the nearby neighborhood generates a sense of optimism, comfort, and triumph. Not only does she use her art to beautify the glorious parkland of St. Nicholas, a celebratory ethos pervades the wooden structure with its multiplicity of colors and shaped panels that echo the inherent diversity of peoples & cultures of this historic community.

Fitgi Saint-Louis’s Fe Limye was sponsored by BEAM Center and the work was fabricated by the devoted team of Em Eason, Akib Chowdhury, and Horatio Mottola.

Jackie Robinson Park – An Ngoc Pham (Vietnamese, b. 1960)

Wooden Insect Human (2025) is a larger-than-life, fantastically animistic sculpture with which one may sit. The seated figure is a slender creature comprised of a stump-like torso, cubical waist, rectangular limbs, curvaceous head, projecting antennae, and stretchy fingers. The open-armed gestures and relaxed position makes the Wooden Insect Human come across as inviting, a comforting beckoning to keep them company. Two sculptural books are also included in the work seen over the bent knee, with one of the titles being a reproduction of the cover for The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees by Douglas W. Tallamy (2021), a text celebrating the wonders of oak trees and proper ways of exercising stewardship for their preservation.

An Ngoc Pham, a Vietnamese refugee who was originally a member of the 1990s Asian-American artist-activist collective Godzilla, utilizes this sculpture to raise awareness about the necessity of protecting our environment. For this particular subject, the Wooden Insect Human’s columnar appearance is similar to that of a tree, and even its extended arms, fingers, and antennae have a branch-like quality to them (a bird landed on one of the arms, but flew away before I could capture a photo of the moment). With deforestation being one of the most egregious disruptors of the environment, Pham’s sculpture’s placement in the middle of a lush park setting wields a guardian-like energy.

This may be coincidence, but it just so happens that on Monday, August 4th, there will be a tree counting event in Jackie Robinson Park from 10am – 12pm in which volunteers will collaborate with the NYC Parks & Recreation division to update the park’s annual tree census. Perhaps the volunteers should consider paying a visit to our anthropomorphic friend for great success in this year’s tree count? Here is the link for the event:

Corner of Broadway & W. 148th Street / Broadway Malls – Iliana Emilia Garcia (Dominican, b. 1970)

The location for this next work is a little different from the previous sculptures, as Iliana Emilia Garcia’s abstract work, Trinity (2025), is positioned along the edge of one of the Broadway Malls, thin strips of green spaces that divide the north and southbound streets in Hamilton Heights. Three vertical screens of wood are connected to one another, but each are positioned in a tension of inward-outward directions akin to a folding screen. With Trinity attached atop a boxy wooden base, the work’s screens do not function as barriers, but as windows. These openings are represented in the form of diagonal rectangles, triangles, half-trapezoids, and parallelograms of varying sizes.

The unique advantage for the placement of Garcia’s sculpture is that this piece can be seen from a number of angles – passersby on either side of Broadway, anyone who crosses through the Broadway Mall, drivers from any direction, and those with street-facing views from their apartments or businesses. The shaped windows encourage one to take a closer look and see how their perception of the local area is altered from this creative vantage point. I admire the Harlem Sculpture Gardens’ decision in putting Garcia’s work in the middle of a busy intersection in one of the liveliest commercial / residential sections of Hamilton Heights for every person who passes through will have an encounter with Garcia’s Trinity – possibly a passing glance, a curious look over, 360 degree perambulation, or serious meditation (there are nearby benches along the Mall which makes this feasible).

Garcia’s sculpture was fabricated by Gary Linares.

Morningside Park – Motohiro Takeda (Japanese, b. 1982)

Motohiro Takeda’s Harlem Gate (2025) is a site-specific sculptural installation comprising two wooden benches. Yet, a distinguishing characteristic of these benches is that the wood retains much of its original arboreal appearance in that the seats are the curved sides of the tree’s trunk supported by two cubed bases on either end for both seats. Under the cool shade of a nearby tree, these benches provide gorgeously picturesque views from either direction one chooses to face: on one side, there is the awe-inspiring pond & waterfall surrounded by mossy, drooping trees reminiscent of a French Impressionist landscape, and on the other a view of tall, aged trees before a backdrop of low-lying, Beaux-Arts / Renaissance Revival apartments from the early-20th Century.

Like Conway, Takeda’s sculptures (and much of his other work) have been created with the shou sugi ban method (here is a link to a video showing a dramatic presentation of his process from 2022). Although in this case, it seems a little more subtle in its usage compared to the charred, rusticated aesthetic found on Conway’s Grid Lines. Takeda’s approach in this work has been to repurpose the tree by transforming it into two benches whilst reminding us of its original form. The specificity of Harlem Gate’s position in a section of Morningside Park with some of the most beautiful views humbly asks of us to commune with nature by understanding the symbiosis of our relationship with such organic phenomena.

Non-Wooden Sculpture Honorable Mentions:

Montefiori Square – Shervone Neckles (Caribbean-American, b. 1979)

Shervone Neckles’s Beacon (2025) is a terrific embodiment of the term “Eureka!” as this is a polycarbonate, concrete, and cast resin sculpture whose central opening is in the shape of a gigantic LED lightbulb. This is not just for show as Beacon is a fully functioning light source that provides sidewalk-level illumination for the open-spaced walking area of Montefiori Square. A lightbulb is often symbolic of a fresh idea or a spark of inspiration. Neckles’s enlarged representation of the object, aptly titled Beacon, seems to have the power of a lighthouse with its verticality and commanding presence, a physical manifestation of a guiding light.

This work was completed in collaboration with the BEAM Center and Lewis Latimer House Museum.

Morningside Park – Michael Levchenko (Ukrainian, b. 1976)

Along a shaded path that crosses between a rocky, forested section to the right and a basketball court to the left, Michael Levchenko’s Post Tango (2025) is a cerise-toned sculpture of an elephantine abstracted figure whose body is composed of intersecting circular discs and ovoid edges that evoke a vibration in the subject’s implied movements. In the midst of a predominantly green area with nearby black fences and brick-colored buildings, Post Tango’s bold coloration makes for a pleasing contrast with both the built and natural environments.

Morningside Park – Graciela Cassel (Argentinian)

After exploring Takeda’s Harlem Gate, be sure to turn around as you will immediately spot Graciela Cassel’s fiery orange Romance in the Garden: Pergola of Hope (2025), another benched work, but this time combining wood, plexiglass, and solar panels. These warmly saturated seats are an ostentatious take on the decorative metalwork seen in garden seating – especially those from France with their lacy, floral patterns. An arched pergola ensconces each of the three seats and these, too, face in the direction of Morningside Park’s pond & waterfall. Sculptural seats are an artistic marvel as these are works that not only compel one to study and admire its form, but to directly engage with it and, considering its context, appreciate the wonders of its surrounds.

Conclusion

Through this focused list of sculptures encountered in my trek through West Harlem on an immaculately cloudless day, I resolutely believe these sculptures and the intent behind their curation effectively embody the Harlem Sculpture Gardens’s mission in providing greater access to art for members of the local communities. Each work has their own story to tell, yet a throughline that I detected (and am certain is the case with the other works beyond my article) is that these sculptures are a gift to their respective neighborhoods that will enrich any and all who interact with them. The importance of public art has me thinking about a moving video from 2005 of the French husband-and-wife artists Christo & Jeanne-Claude in Central Park. They were approached by a pedestrian after installing their Gates installation in which he thanks them for providing a service to New York by making their art accessible to everyone and then states that art is inherently “good for the soul”. Needless to say, the artists involved in the 2025 cohort of the Harlem Sculpture Gardens program have used their artistic talents to nourish our hearts, minds, and souls.

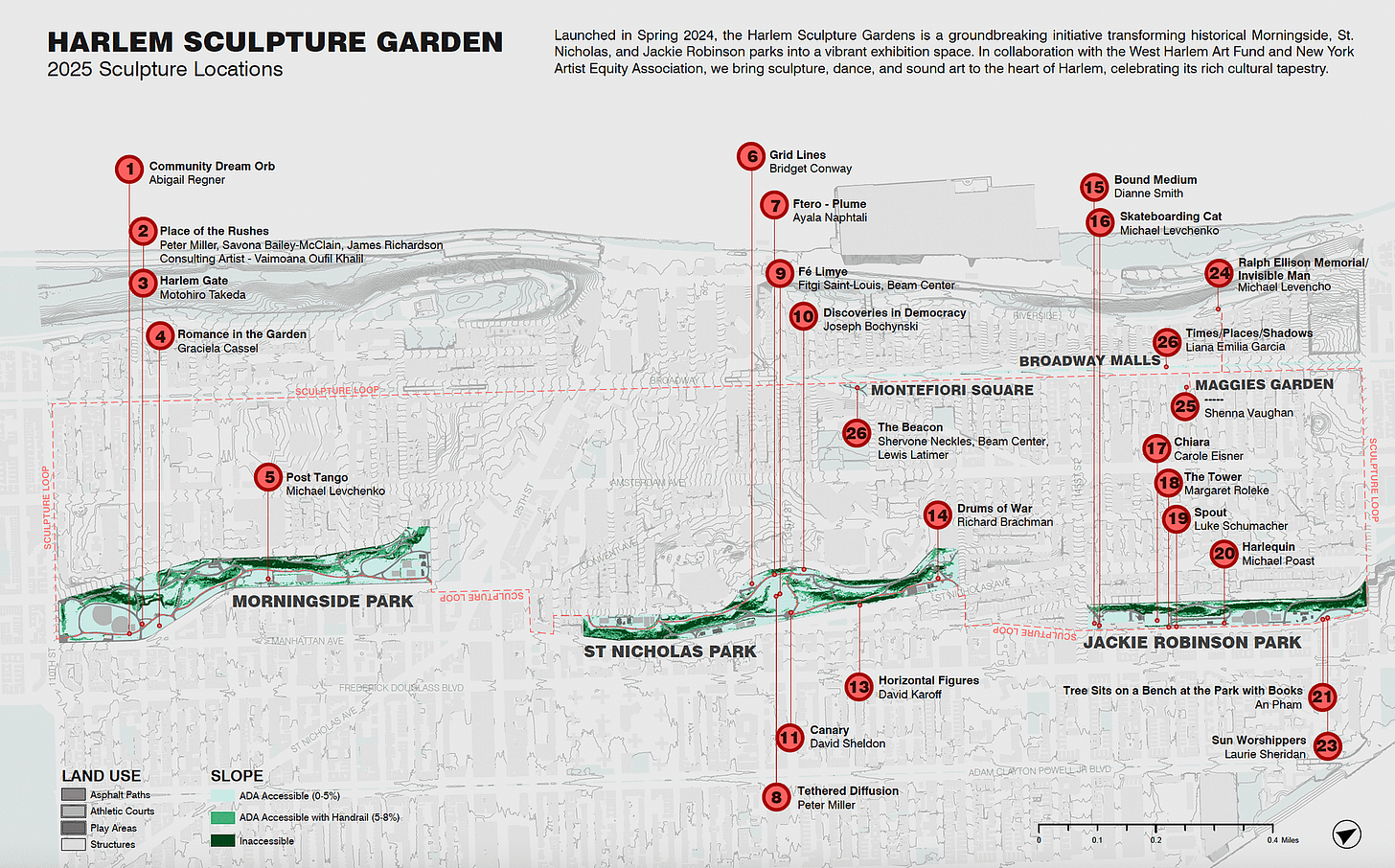

For those of you keen on exploring these and the rest of the sculptures in the Harlem Sculpture Gardens program, below is the link to the website and an image of the map that pinpoints the precise locations for each sculpture. This program was made possible through the West Harlem Art Fund and New York Artists Equity Association.