Lincoln Theatre

58 W. 135th Street, New York, NY 10037

The Lincoln Theatre was a theater located on 135th Street near Lenox Avenue in Harlem, New York City. One early performer, around 1903, was Baby Florence, the child singer and dancer who grew up to be Florence Mills, the Broadway and London star.It opened in 1915 and was the first theater in a then predominantly white neighborhood in Harlem to cater to black audiences. The theater (now Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church) reached its peak of fame in the 1920s, when entertainers such as Bessie Smith, Florence Mills, and Fats Waller headlined. (Fats Waller had been hired as the organ player of the theater when he was fifteen years old.) The Lincoln Theatre was the only place in New York where Ma Rainey performed.

The theater was originally a nickelodeon called the Nickelette. In 1909, the building was purchased by Maria C. Downs, who increased the seating and changed its name to the Lincoln Theatre. Due to the Great Migration happening around this time, more African Americans were moving to Harlem; however, many of the theaters in Harlem were segregated or completely closed to black audiences.

Downs turned the Lincoln into a headquarters for black shows and audiences, a policy so successful that she constructed the building with a seating capacity of 850 in 1915.

Although the theater placed some emphasis on serious drama—with the Anita Bush Stock Company, for example, before it moved to the rival Lafayette—the Lincoln during the 1910s and 1920s became the focal point for down-home, even raucous, vernacular entertainment that particularly appealed to recent working-class immigrants from the South. As the New York showcase of the Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA), it drew all the big names of black vaudeville: Bessie Smith, Bert Williams, Alberta Hunter, Ethel Waters, and Butterbeans and Susie. The Lincoln was the only place in New York where Ma Rainey ever sang. Mamie Smith was appearing there in Perry Bradford’s Maid of Harlem when she made the first commercial recording of vocal blues by a black singer.

Because it housed a live orchestra, the Lincoln also became a venue for jazz musicians. Don Redman performed there in 1923 with Billy Paige’s Broadway Syncopators. Lucille Hegamin and her Sunny Land Cotton Pickers featured a young Russell Procope on clarinet in 1926, the same year Fletcher Henderson with his Roseland Orchestra played there. Perhaps the name most closely identified with the Lincoln was the composer and stride pianist Thomas “Fats” Waller, who imitated the theater’s piano and organ player while still a child and was hired for twenty- three dollars a week in 1919 to replace her; he was then fifteen years old. When he failed to find financial backing to produce his opera Treemonisha, Scott Joplin paid for a single performance at the Lincoln. Unable to afford an orchestra, he provided the only accompaniment himself on the piano.

A steady stream of white show-business writers and composers, including George Gershwin and Irving Berlin, joined the black audiences at the Lincoln, not only to be entertained but to find new ideas and new tunes. More than one melody, dance step, or comedy routine that originated with a black vaudeville act wound up in a white Broadway musical. The Lincoln did not survive the economic disaster of the Great Depression and the changing tastes of the Harlem community, where more sophisticated people began to refer to it as “the Temple of Ignorance.” Downs sold the theater in 1929 to Frank Shiffman, who turned it into a movie house.

Lafayette Theatre (1912–1951), 2225 7th Avenue, known locally as “the House Beautiful”, was one of the most famous theaters in Harlem. It was an entertainment venue located at 132nd Street and 7th Avenue in Harlem, New York.

The Lafayette Theatre opened in November 1912 as a legitimate theatre which also presented vaudeville. By 1914 it was a vaudeville & movies theatre. It stood on Seventh Avenue (now Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Boulevard) at 132nd Street in Harlem. It was one of the first theatres in New York City to de-segregate and allow African-American theatre goers to sit in orchestra seats instead of only in the balcony. Later, like so many other former live theatres, the Lafayette Theatre switched to movies.

October 17, 1921 the Cast of Shuffle Along performed at the Lafayette Theater in Harlem to benefit the NAACP.

Video about Shuffle Along — https://vimeo.com/21251492

A project of Meyer Jarmulowsky, a Lower East Side banker. V. Hugo Koehler, an established theater architect, designed the two-story, 1,500- seat theater in the Renaissance-style and flanked it with two three-structures at the corners of 131st and 132d Streets for stores, offices and meeting rooms.

At the time, Harlem’s real estate market was depressed and many owners had begun to rent to black tenants apartments that previously had been let only to white tenants. The Age, a Harlem newspaper, reported that the racial character of the area was shifting, with 132nd Street recently black and 131st still white.

The Lafayette allowed blacks only in the balcony and the bitter complaints in The Age and elsewhere document the state of black consciousness in New York at the time. By August 1913 blacks were allowed in the orchestra but had to pay double the white price of 10 cents, 5 cents for children.

But the theater had trouble making money and that year became the first major theater to desegregate, according to Jervis Anderson’s “When Harlem Was In Vogue.” In October 1913, a troupe called the Darktown Follies opened “My Friend From Kentucky” and the audience was 90 percent black.]

Lester Walton, drama critic for The Age, voiced optimism that an increase in black audiences would produce a corresponding increase in serious black productions.

In 1914, Walton was named manager. The 1915 opening of “Darkydom” attracted Irving Berlin, John Cort, Charles Dillingham and, reported The Age, a variety of “names which might be seen on the Social Register.”

In 1916, the black actor Charles Gilpin established the Lafayette Players, Harlem’s first black legitimate theater group, at the Lafayette, and Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, Moms Mabley, Leadbelly, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Earl Hines, Stepin Fetchit and others performed there.

The theater was closed in the 30’s, but John Houseman, developing the Works Progress Administration’s Negro Theater Project in New York, took it over for an effort that ultimately employed 200 black performers. In consultation with Virgil Thomson, Mr. Houseman planned two types of works: plays written, produced and directed by blacks — like “Walk Together

Chillun!” and “Conjur Man Dies” — and classical works adapted to black circumstances.

THE first of this latter group, directed by the 20-year-old Orson Welles, was “Macbeth,” set in Haiti and soon dubbed “Voodoo Macbeth.” It played to full houses for 10 weeks, then moved on to Broadway and a national tour.

The Negro Theater Project ended in 1939 and in 1951 the building was bought by the Williams Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, founded in 1919.Around 1950 the Lafayette Theatre was converted to a church. It became home to the Williams CME (Christian Methodist Episcopal) church. By April 2013, the church had moved out and the building was in the process of being demolished. An apartment complex now takes up the entire block. The structure was demolished in 2013.

The Alhambra Theater building is located at 2108-2118 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard (7th Avenue) at the South-West corner of 126th Street in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. Simpson West Realty, LLC, owns the building, as of 2014.

By 1925, Alhambra Theater catered to its Black audience members. One of its highlights was when the theater held a Harlem premiere of Blackbirds of 1926. It was a six-week engagement musical revue that was produced by Lew Leslie to show off the talents of Florence Mills.

Gem Theatre

Gem Theatre

36 W. 135th Street, New York, NY 10037

Designed by architect Maximilian Zypkes, the Crescent Theatre opened December 16, 1909 with a program of vaudeville and motion pictures. It was a mixed-race movie theatre. It continued to exhibit films through at least 1922, by which time it was known as the New Crescent. In 1925 it was renamed Gem Theatre and operated as an African-American movie theatre. By 1930, as the New Gem Theatre and was closed around 1935. By 1937, the space was being used as a meeting hall.

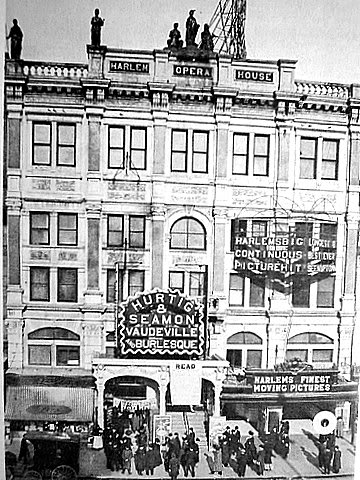

Crescent Theatre 50 W. 135th Street

The opening night of the Crescent, on the December 16, 1909 — hailed as a “first class vaudeville and moving picture house” — turned out to be so successful that many patrons had to be turned away. This pioneering cinema stood at 50 W 135th Street. We know that another theater, the Lincoln, situated on the same block, opened around the same time, so competition was fierce from the outset. Scholars do not agree as to which venue was first, but the Lincoln was probably the predecessor (unless it opened in the last 15 days of 1909).

A prominent Black film critic, Lester A. Walton described the Crescent as a place drawing a diverse clientele, where “white and colored sat side by side, elbowing each other” and where Black ushers made no attempts to interfere by separating the races. Walton was optimistic: soon enough, he reasoned, all theaters would be prompted to institute equally inclusive policies.

Advertising for a biblical feature Daniel (1913). Was it screened at Crescent? We have no hard evidence, but Vitagraph was a New York-based studio known for its sophisticated productions, so it is likely.

Unfortunately, we know very little about the types of photoplays screened at the Crescent, because most of the publicity and subsequent reviews revolved around the vaudeville show. The only source containing details that go beyond mentioning the simple fact of moving pictures comes in January 1910, with the advert promising “at least one Vitagraph picture daily.” The brevity with which the publicity dealt with the movies was by no means unusual. These one-reel features, which tended to run about fifteen minutes in length, changed so frequently there was little incentive for cinemas to describe them in much detail.

Although the Crescent’s history proved short, as increasing competition drove the owners out of business by 1915, its trailblazing impact on local entertainment was vast. Some historians point out that in staging established, sophisticated productions such as the opera The Tryst, the venue initially aspired to appeal to middle-class customers. Opinion pieces in the local press continuously alluded to its reputation as a bastion of safe entertainment: “When patrons go to the Crescent Theater they expect to see a clean show. Those who want to see a muscle dance exhibition and hear a lot of raw talk know where to go for it.” At a time when moving pictures houses were still fairly new — and perceived as trite, or even vulgar — this was an important statement. In the following decade, the building would house another cinema, the Gem.

Leave a comment